Orchids have been a source of fascination for plant lovers for centuries. Some species seem to adapt effortlessly to indoor life, while others stubbornly cling to their wild nature. This raises an intriguing question: how far can you actually "tame" a plant? And where is the line between natural adaptation and human manipulation?

The first steps toward domestication

Domestication of plants began thousands of years ago, when people began selectively breeding based on traits such as growth rate, fertility and appearance. With orchids, this movement came relatively late, mainly because many species require complex growing conditions. Nevertheless, there are now several orchids that are so well adapted to culture that they can bloom even in a windowsill far away from their original habitat.

A good example of this is the Phalaenopsis, so-called butterfly orchid. Through generations of selection and crossbreeding, this species can now withstand less ideal conditions, such as drier air and fluctuating temperatures. The Phalaenopsis is thus one of the first orchids that can truly be called domesticated.

Stubborn survivors: the limits of breeding

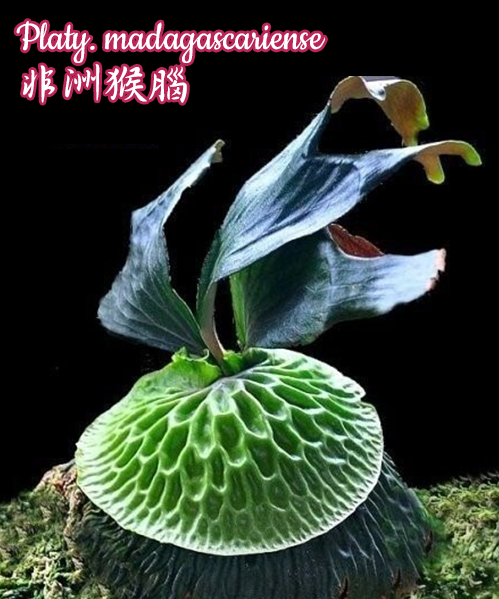

However, not all orchids give in so easily. Some species, such as Dracula, Masdevallia or certain Paphiopedilum-species, stick strongly to their specific requirements. For example, they require extremely high humidity, very cool temperatures or a subtle balance of shade and air movement. If these conditions are not just right, they languish, no matter how carefully they are cared for.

This persistence shows that domestication is not a natural process. Biological complexity, ecological dependencies and genetic limits all play a role in how far a plant can be "molded" to human desires.

Domestication versus manipulation

An important ethical issue arises here: when does cultivation turn into manipulation?

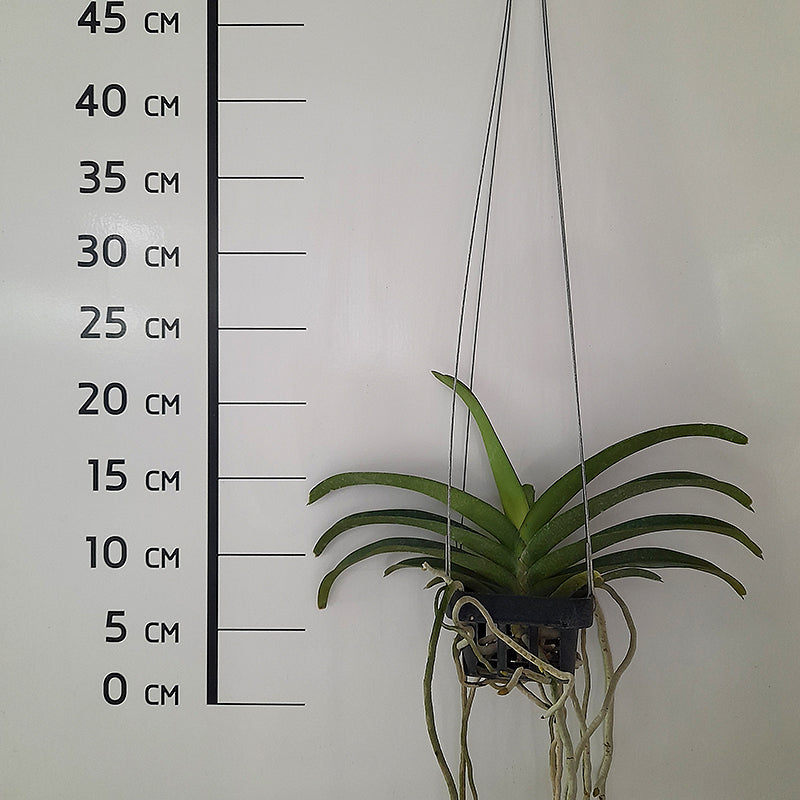

In many commercial orchids today, more than selective breeding is taking place. There is active intervention in the genetic material through tissue culture, mutagenesis or even genetic modification. This creates, for example, miniature varieties, extra sturdy flowers or varieties with unusual color patterns.

While these techniques have greatly enriched the assortment, it also raises the question: are we still staying within the natural boundaries of the species, or are we creating something fundamentally new? And what are we losing in terms of genetic diversity and natural resilience along the way?

What we can learn

Orchids make it clear that domestication is not a linear or unlimited process. Some species adapt slowly; others remain true to their origins. And sometimes the limits are not only biological, but also ethical: how far are we really willing to go in "adapting" life to our preferences?

So the orchid teaches us something not only about plants, but also about ourselves: about our drive for beauty, control and perfection. And it teaches us about the respect that wild nature sometimes still manages to command, even in our most controlled environments.